Illustration 2: The concepts

Working with students

The Australian Curriculum: Geography and its state-based iterations (including HASS) draw on seven key concepts:

- place

- space

- environment

- interconnection

- sustainability

- scale

- change.

They are the 'big ideas' that can be applied across the subject to identify a question, guide an investigation, organise information, suggest an explanation or assist decision making. They are also the concepts central to a discipline that increasingly engages with the humanities as well as with the physical and social sciences.

Fifty years ago geographers approached the discipline through four traditions – spatial, area studies, earth sciences and people-environment interactions. Forty years ago they viewed the subject through six intersecting paradigms – spatial organisation, spatial diffusion, landscape, ecosystem, regional studies, and environmental perception.

Today, the core of geography is expressed through its key concepts, and the seven listed above have now been identified as central to the study of geography in Australian schools.

This approach is consistent with that adopted elsewhere. New Zealand education authorities, for example, list seven concepts in senior secondary education, the United States of America identifies six 'essential elements' and the United Kingdom has seven key concepts.

The Institute of Australian Geographers identifies three complementary concepts:

- place

- environment

- space.

Recommended readings

- F–6/7 Humanities and Social Sciences – Concepts for developing geographical thinking [http://docs.acara.edu.au/resources/F6_7_HASS_Concepts_for_developing_geographical_thinking.pdf]

- The key concepts or big ideas in geography [http://seniorsecondary.tki.org.nz/Social-sciences/Geography/Key-concepts]. The New Zealand Ministry of Education provides details about their model of geographical concepts.

- What is geography? [https://www.iag.org.au/what-is-geography-]The Institute of Australian Geographers provides information on the nature and extent of geography.

Classroom illustrations

The seven geographical concepts of place, space, environment, interconnection, sustainability, scale and change are the key to understanding the places that make up our world. These are different from the content-based concepts such as weather, climate, mega cities and landscapes.

As such, the Australian Curriculum: Geography's seven key concepts can be thought of as second order rather than substantive concepts. Second order concepts organise and shape questions within the discipline of geography rather than identify the content to be addressed.

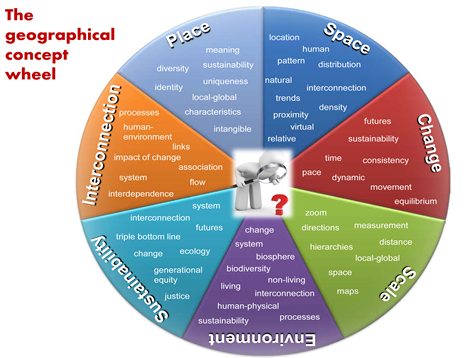

There are many other ways of classifying concepts. One is to organise concepts in a hierarchy with the big ideas occupying superordinate positions and others in subordinate positions. The geographical concept wheel (see below), developed by Malcolm McInerney, identifies seven big ideas and a number of subordinate concepts.

Students can learn subordinate geographical concepts informally but some abstract concepts, such as the spatial concepts of relative and absolute location, need formal teaching approaches.

Examine the GEOGstandards video [GEOGStandards material to be added to the AGTA website] where an accomplished geography teacher formally instructs Year 9 students with regard to relative and absolute location.

Questions for discussion

- Jeana Kriewaldt, a geography educator at the University of Melbourne, has classified geographical concepts as either 'descriptive or substantive', or, 'analytical or syntactical'. Read: The quest for concepts: Searching for the key ideas in geography

How would Kriewaldt classify the Australian Curriculum: Geography concepts?

- Explain the hierarchical assumptions that put location, distance and distribution above spatial association, spatial interaction, movement, spatial change over time, and region.

- David Leat, a geographical educator from the University of Newcastle, United Kingdom, concerned with thinking through geography, arrived at the following concepts:

- cause and effect

- classification

- decision-making

- development

- inequality

- location

- planning

- systems.

To what extent do these concepts assist in thinking about the Australian Curriculum: Geography concepts?

- United Kingdom geography educators David Lambert and John Morgan see geographical concepts as points of contestation with multiple meanings that cannot be reduced to single straightforward definitions.

- Review the three ways by which the concept of space is understood in the Australian Curriculum: Geography.

- If space can be socially constructed, then so can scale. Demonstrate how 'scale' is perceived differently by different people and by different organisations.

- Educational psychologist Jerome Bruner placed great emphasis on the style of presentation from the enactive to the iconic and symbolic.

- How do fieldwork, the use of models and the visual enable students to grasp the complexity of geography's more abstract concepts?

- How can deep understanding of geography's big ideas bring students to the point where they are able to tackle unfamiliar problems?

- Consider how the key questions posed in geographical inquiry limit or liberate guiding ideas or concepts. A question about where the phenomena are located may reveal concepts about location, distribution, pattern and spatial association. However, a question about what issues should be considered in decision-making may result in an examination of concepts about planning, values, perception, social justice, intra-generational equity, liveability and spatial justice.

Reflective questions

- Reflect on the following: 'Before you can teach a concept successfully, you must thoroughly understand it yourself' (Lang, McBeath, & Hebert, 1995, p. 192).

- The term 'landscape' has multiple meanings. How is landscape understood in the Australian Curriculum: Geography?

- What is the difference between a study of place and the study of places? David Lambert, a UK geography educator, has referred to the former as part of the 'grammar' of geography and the later as its 'vocabulary'. Explain this notion.

- How might the following question stems enable students to better comprehend geographical concepts:

- Can you write it in your own words?

- What is the main idea?

- Can you distinguish between … ?

- What are some of the non-essential characteristics of … ?

- Can you provide an example of … ?

- How might critical analysis of geography's concepts encourage high order thinking?

- What kinds of background and cultural knowledge do students bring to geography's big ideas?

Resources

Clifford, N., Holloway, S., Rice, S. & Valentine, G. (2009). Key concepts in geography (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Hall, R. (1982). Key concepts: A reappraisal. Geographical Education (4), pp. 25–34.

Henderson, D. (2011). Concept building. In C. Marsh & C. Hart (Eds.). Teaching social sciences and humanities in an Australian curriculum. Frenchs Forest: Macmillan Education Australia.

Kriewaldt, J. (2012). Why geography matters. In T. Taylor, C. Fahey, J. Kriewaldt & D. Boon. Place and time: Explorations in teaching geography and history. Frenchs Forest: Pearson Education Australia.

Kriewaldt, J. (2004). The quest for concepts: Searching for the key ideas in geography. Interaction 32(3), pp. 29–30.

Lambert, D. & Morgan, J. (2010). Teaching geography 11–18: A conceptual approach. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Lang, H., McBeath, A. & Hebert, J. (1995). Teaching concepts. In H. Lang, A. McBeath & J. Hebert. Teaching strategies and methods for student-centred instruction. Sydney: Harcourt Brace, pp. 73–194.